Developing ropes is like everything else – the idea comes first. A developer or test climber may often be dissatisfied with a particular rope while climbing. Too heavy, too thick, or difficult to handle? With a little luck and perseverance, his ideas on how to improve performance get translated into better ropes.

“You have to take your dreams into the office and start thinking about them,” says new Ocún rope developer Radim Feix. “At the beginning you also have to get the right material for the core and braiding. It’s usually polyamide and you have to choose a particular type. As for the other materials, I generally don’t disclose that... trade secrets and all.”

The structure of polyamides used for the sheath and for the core differ on a molecular level and also in terms of fineness. Note that fineness is not subjective in the rope industry, it is a clearly defined quantity, measured in grams per unit length, usually per kilometer.

In the case of ropes, the development phase involves machines rather than computers, only the colored braid patterns are designed using graphics programs. “Textiles are not entirely predictable, one simple change of strand in the weave and the rope might not be strong enough” says Radim, explaining why that is.

It´s not just about weaving

The first operation with the material is called plying. Plying creates the yarn, the individual strands that are later woven into the core or sheath. Plying is carried out for both the core and sheath on plying machines. All fibers are given a pre-defined twist, strength and tensility. This is a mechanical process after which the fibers are dyed and wound onto spools.

It is then time for the most important operation, which is called shrinking. The details of the shrinking process are closely guarded by every manufacturer. “During shrinking we subject the polyamide fibers to pressure, moisture and temperature to give it its dynamic qualities.” Simply put, without shrinking we would have a static rope. Shrinking makes the rope dynamic – and only dynamic ropes are suitable for climbing, because when a climber falls the rope stretches and softens the fall.

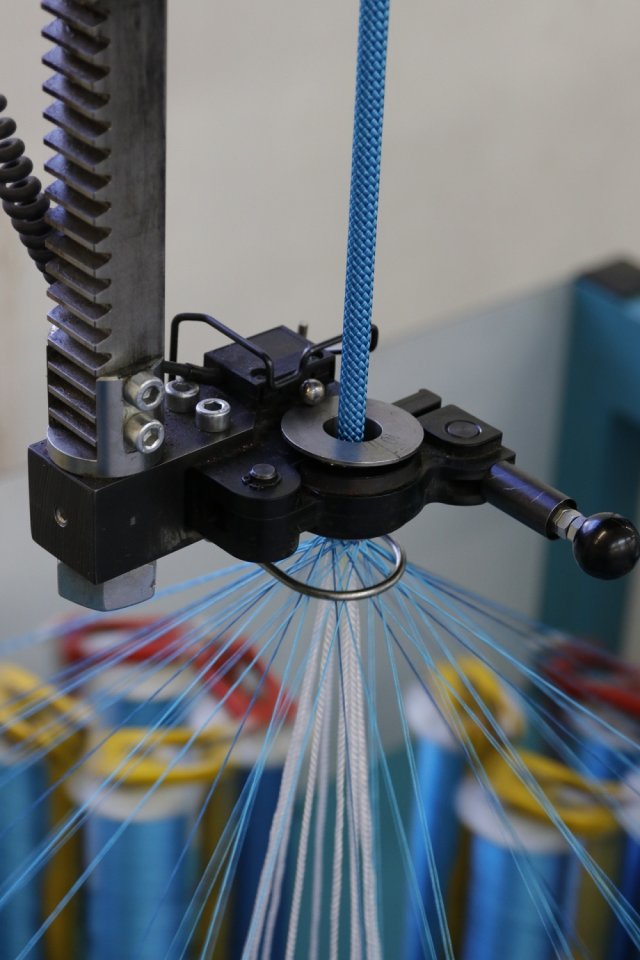

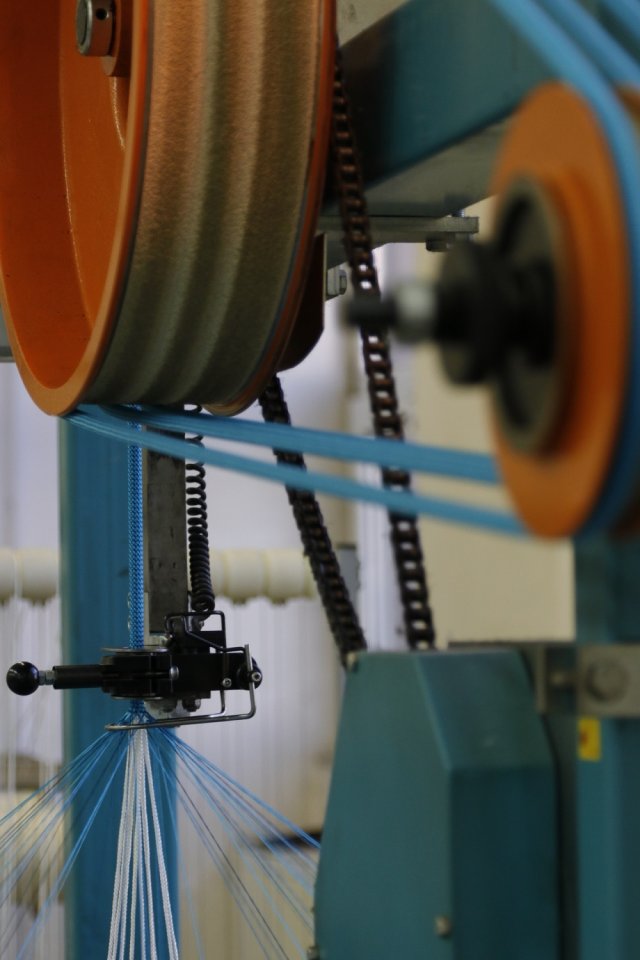

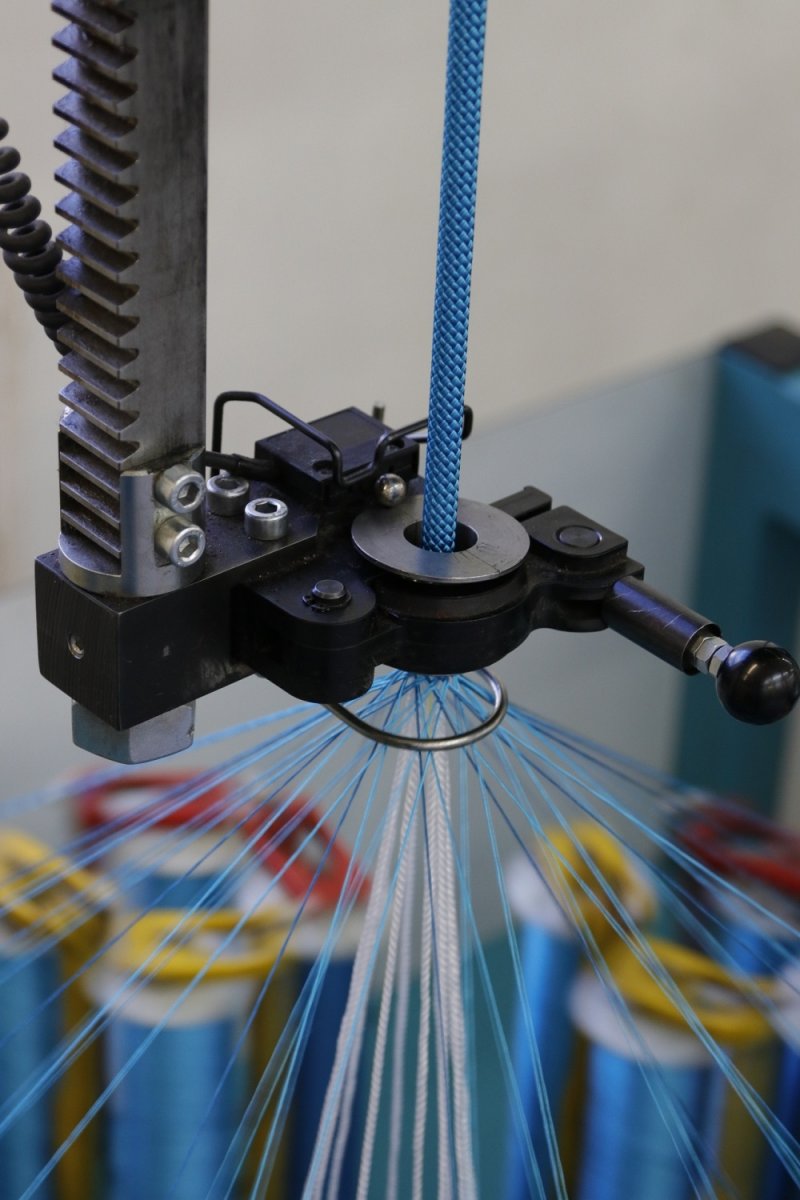

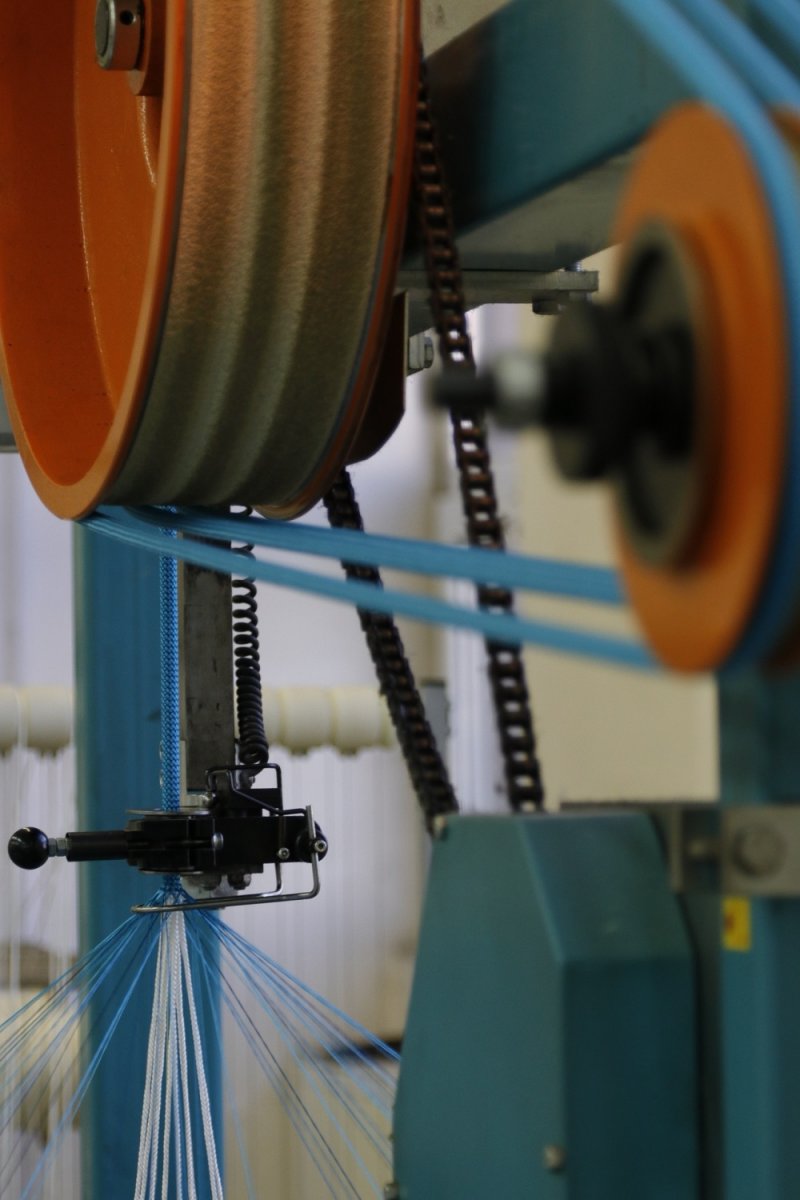

When the shrinking process is completed, we send individual fibers to the weaving machines, where they become the core and the sheath. “A huge advantage of our ropes is that we constantly monitor the tension in all strands,” says Radim. Since we monitor the tension in every strand of each rope, we can guarantee balanced quality. Even if individual yarns were drawn from spools at the same speed, their tension would gradually change simply because a full spool has a different diameter than one unwound halfway. Super Tension Control is what enables us to thoroughly monitor tension in fibers.

Once the rope is woven, a protective layer is applied to the sheath. This makes the rope more resistant to the penetration of dirt and thus extends the life of the rope. At Ocún we use technology that is free of PFCs (water-repellant perfluoro-hydrocarbons), which is more environmentally friendly.

Which is the optimal diameter for your sends?

We are now introducing a collection of four new ropes designed for on-sight climbs, working on your routes, beginning climbers and climbing gyms. All four share the same manufacturing processes and technology for processing fibers. They only differ in terms of target group. So which diameter is the best for you?

- Vision 9.1:A rope for performance climbing. Every gram saved will help you get to the top

- Spirit 9.5:The optimal balance of diameter, weight, and durability for the experienced all-around climber.

- Cult 9.8:An excellent choice for beginners and advanced climbers alike. Durable and very comfortable to handle.

- Guru 10:A rope for regular trainings in the climbing gyms and beginning climbers. It lasts longer than the others, you can fall to your heart’s content and it can handle thousands of meters climbed with frequent abrasion over edges and through anchors.

What kind of route is difficult enough to justify our super-light 9.1 mm rope? That’s subjective. What might be a 9a+ for a stud on the cover of a magazine might be a 6b for a hobby climber. And if shedding a few ounces gives him wings, why not? It is also important to see how the rope feels and make sure it is compatible with your gear. Certain semi-automatic devices can only be used with ropes within a clearly specified range of diameters.

Rope dictionary

- Core = It´s called a soul of the rope by the workers in manufactories. A single one of the core´s strands can bear a static load of over 100 kg; the total load capacity of the rope also depends on additional factors – fineness, fiber twist, etc.

- Sheath = The sheath covers the core and its primary purpose is to protect the core, and to a small degree it also contributes to the load capacity of the rope.

- Ply, plying = The creation of yarn from polyamide fibers. This takes place on plying machines, in parallel for yarn of the core and sheath. Plying gives yarn a certain number of twists per meter.

- Spool = The spool onto which the plied yarn is wound.

- Weaving = Plied yarn is then woven to create the rope.

- Shrinking = The exposure of polyamide fibers to pressure, moisture and temperature. The effects of shrinking give polyamides their dynamic qualities.

- Fineness = An important value for the textile industry. It expresses the length weight of the yarn and is given in units called tex [g/km].

- Rope tensility = Given in %, this indicates how much the rope stretches during dynamic testing.

- Number of UIAA falls = Ropes are tested on fall machines that maintain a prescribed fall factor (this is significantly greater than the fall factor of the majority of conceivable falls that could happen during actual climbing). The UIAA fall number is the lowest measured number of falls that a particular model of rope withstands during repeated testing.

Useful tips and tricks

Uncoil your new rope. The first thing you must do with a new rope (after posting a picture on Instagram with #ocun), is to properly uncoil it. Otherwise it will kink and the first few climbs will be a belayer’s nightmare. That’s because during production ropes are wound onto spools and they retain this shape. There are several ways to uncoil your new rope, e.g. you can take the new rope in one hand and uncoil it by alternating three coils to the right and three to the left. The main thing is for the entire rope to pass through your hands and get straightened out.

Alternate ends. Your rope will last longer if you alternate the ends you climb on to make sure it wears evenly. This is easier with new Ocún ropes because each end has a different color code.

Check the length of rope when rappelling. “I’ll get a rope” says one friend, who instead of his own sixty-meter rope mistakenly grabs his girlfriend’s fifty-meter rope. It sounds like basic stuff, but a mistake as simple as this has caused countless accidents. Our ropes are color coded for every length to make climbing much safer.

Check your rope. Visually and by feel. Is it smooth, is the sheath torn anywhere? Is the entire rope approximately the same toughness and diameter? Once in a while an inspection is in order. Pay particular attention to the last few meters of the rope at the ends where falls are caught. Also look for signs of abrasion against sharp edges or from falling rocks.

Cut early. If the sheath becomes damaged, cut the rope. Not because it suddenly would no longer have sufficient load capacity, but because it is more susceptible to further damage. As soon as the sheath is damaged somewhere, the core is at greater risk. After cutting off the end, mark the middle. This should only be done with a rope marker that will not damage the rope. Every one of our new ropes comes with a free rope marker.

Never climb on a wet rope. And especially not one that is frozen. Water and ice fundamentally alter rope properties, and not for the better. In extreme conditions it is possible to rappel down a wet rope to safety.

Find a good storage place for your rope. The ideal storage place is dry and dark without temperature extremes. Proper storage will extend the rope’s life. If your rope was used in freezing conditions, let it warm up before storing. Ropes should not be left to bake in the sun for long periods or placed near heat sources.

Ropes get soft. A completely new rope generally feels slippery and hard. Over time this changes. Most ropes reach their optimal condition after a few weekends of climbing – just the right softness and the right speed (when passing through a belaying device).