No manufacturer will tell you the exact recipe for their sole rubber. Neither will we dictate to you the detailed composition of the new CAT sole. So let us at least draw open the curtains of the rubber laboratory a little to let in more light on how the rubber is actually made.

It takes years to develop a good mixture. Analyses, dozens of trials, hundreds of tests... Over and over again until the moment comes when everything fits and the result is rubber that meets the predefined requirements. These must be formulated by a climbing shoe developer in collaboration with a team of test climbers – they know best what will help them not to lose their balance on crumbly friction routes or keep their footing on small footholds.

The development takes place in a rubber laboratory - the most suitable raw materials are selected, mixed in a device called a kneader, vulcanized into plates, and then tested in the laboratory and on the cliff face.

Recipe for sole rubber

The starting materials for rubber mixtures are now made mostly synthetically. Natural rubber or caoutchouc is still obtained by making incisions in the bark of rubber trees, but the vast majority of rubbers are made by chaining hydrocarbons derived from crude oil. But rubber is not only caoutchouc. Did it ever occur to you that soot is also important for it?

Main ingredients:

- Synthetic caoutchouc

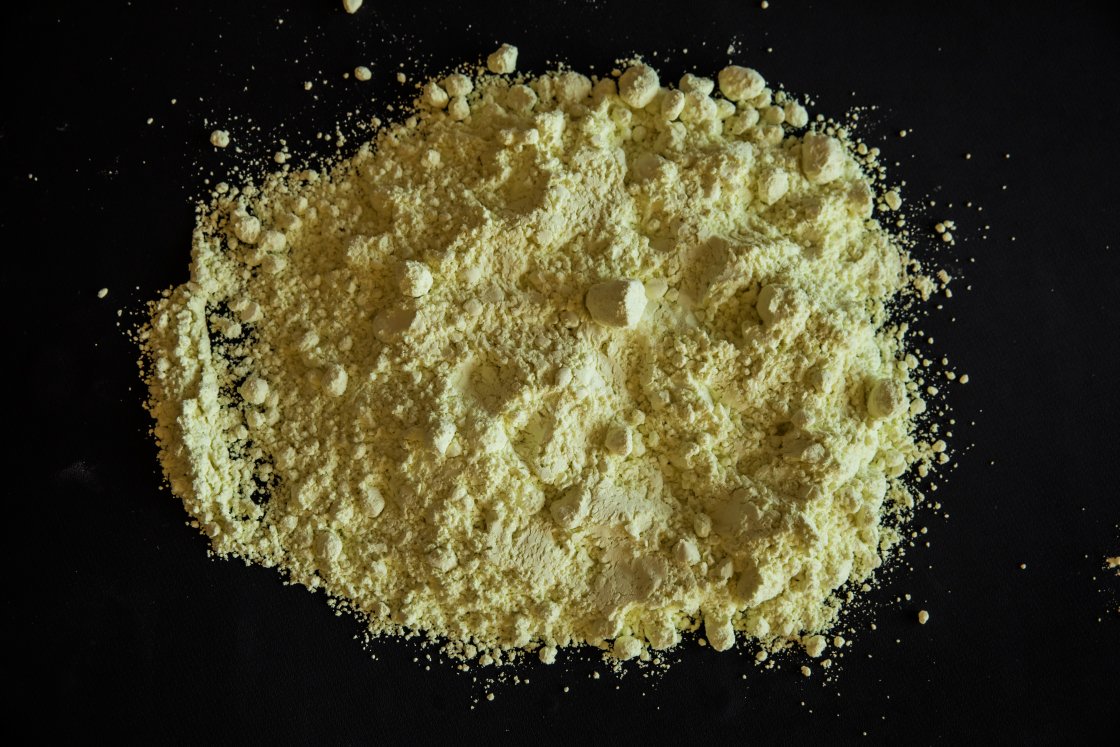

- Soot

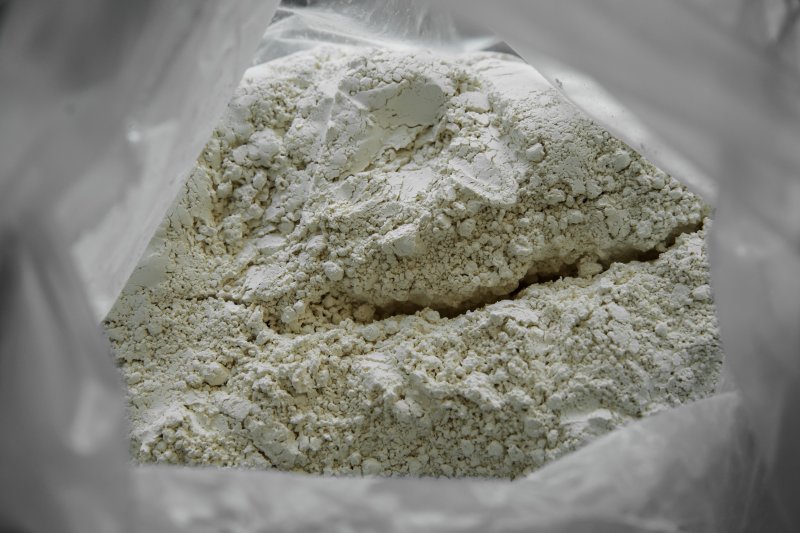

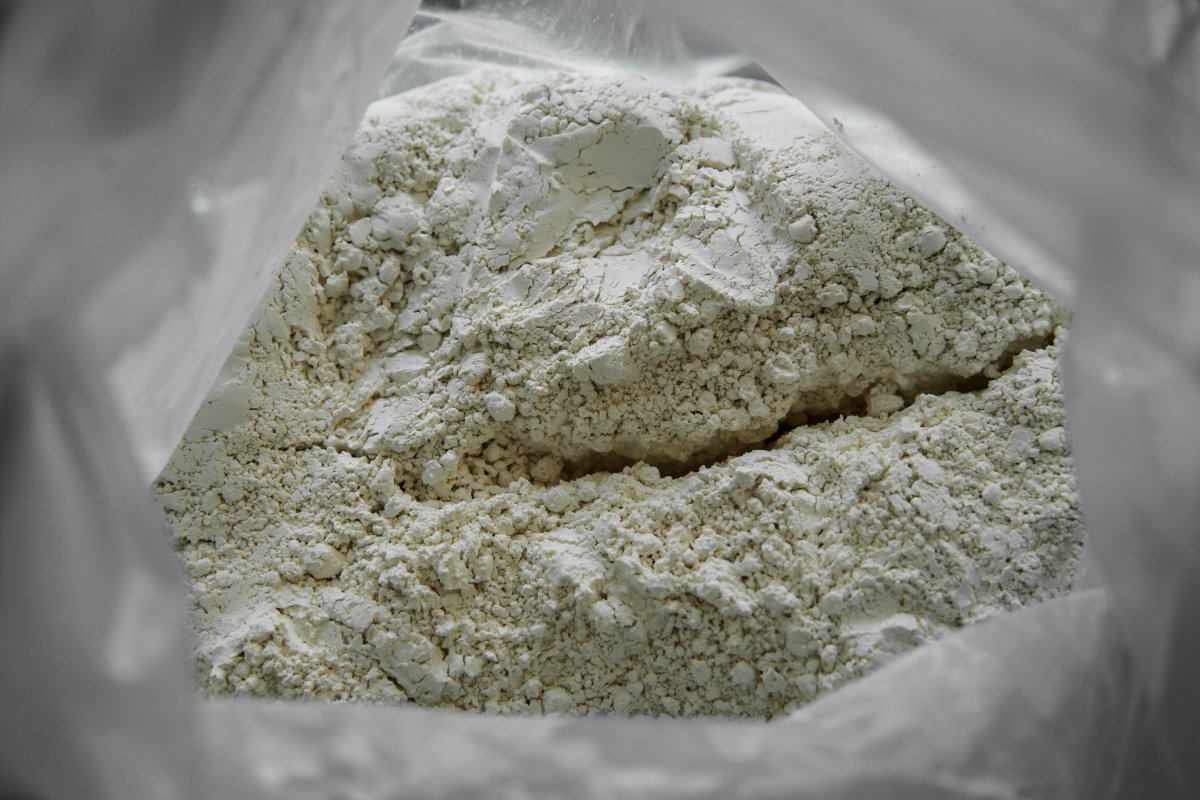

- Light fillers (mainly quartz)

- Paraffin

- Antioxidants

- Softeners

- Vulcanization system (sulphur and vulcanization accelerators)

Natural rubber is a fascinating material whose discovery at that time gave rise to a small technological revolution. But it has several disadvantages, and therefore we prefer to use its synthetic variant. This is produced by polymerization of hydrocarbons and exhibits more stable properties over a wider temperature range. It does not soften so much when hot, while in winter it stiffens less. Every boulderer ready to climb even at minus 5°C will appreciate it.

Just as rubber is now mostly produced synthetically, we do not obtain soot by sweeping chimneys. In fact, it really matters what it is like and cannot be just any sort. It is obtained by incomplete combustion of pre-selected input materials. Also thanks to soot, the rubber has the exact mechanical properties that we want from it. Soot gives it strength and hardness and also increases wear resistance.

In our case, light fillers mean mainly ultrafine quartz. Even quartz is obtained synthetically and we benefit from it - quartz dust, which is generated by controlled crystallisation in the lab, is finer than that from nature.

In the mixture, light fillers play a similar role to that of soot – their suitable combination with soot modifies the properties of the rubber so that the result matches its purpose.

Waxes (paraffins) are also added to the mixture. They make its processing easier and the resultant rubber is more resistant to weathering - waxes flow out to the surface to form a thin film that helps protect the rubber from ozone ageing or blistering.

There are many types of antioxidants and generally they improve the resistance of the rubber against mechanical stress and extend its life. Softeners are only a marginal ingredient of the recipe, much more is added to the foxing rubbers - these are the coloured rubbers that give the climbing shoe its shape.

Vulcanization is the crux

After stirring the mixture in a device called a kneader, a roller press comes next, set to the desired thickness - a few millimetres depending on how thick the soles to be made from it will be. The drawn rubber foils are then vulcanized.

“Vulcanization is a process in which rubber under high pressure is heated to a temperature of about 170°C and obtains the properties that are key for its use in climbing,” explains Martin Sedlák, the climbing shoe designer. In vulcanization, the rubber loses most of its plasticity and becomes an elastic substance without shape memory. Looking closer at the molecular structure of the polymer, it looks like this - its linear chain links to sulphur and they create a 3D network together. All the chains of the input polymer connect with each other and this fundamentally affects the properties of the rubber. In vulcanization, the technologist must control the temperature, pressure, and time - by modifying them he adjusts the process and the result.

In order for the vulcanization to proceed properly, the mixture must contain the vulcanization system, which is the direction of raw materials on a sulphuric basis - yes indeed, sulphur is used in the production of climbing shoes (!). Vulcanization of the sole rubber must take place in such a way that the rubber does not completely lose its plasticity. This makes it possible for the miniature crystals of the granite to dig into it from time to time – as a result the climber does not fall from the rock. Adhesiveness and partial shape memory effect – these two things are keys to success.

In the crag laboratory

When a laboratory sample of rubber is finished and it seems to work, testing will start. We call climbers of all interests and preferences - sandstone climbers, sport climbers, boulderers, those who prefer delicate technical moves as well as those who are focused on maximum strength... We let them try the shoes and listen to their opinions. The blind test is especially beneficial - climbing shoes are equipped with different rubbers, the type is not revealed in advance. Thanks to the blind test we obtain answers unencumbered by prejudice.

After the samples have been successfully tested, mass production can start. Even its results are still tested – it is necessary to confirm the conformity of the large-scale quality with the laboratory. But basically, the working procedure is the same in the lab as in the production. Only the quantities are different – samples are made from 1.5 kg of mixture, while production works with 100 kg as the basic batch. The finished rubber continues to Ocún manufactory where we make climbing shoes from it (you can read the story from our manufactory here).